As I do more photos I’m thinking more and more about what makes this different from anything else I’ve done — why is this different from Librarians or soldiers or anything else. Wrapping my head around the whys makes it easier, I think, for me to push through the doing.

I’ve been fascinated for a while now, really since the very beginning, with masks — and it’s been a central theme of the pandemic too — first their scarcity, then their usefulness then their ubiquitousness … at first we didn’t know anybody who had one, and then we were all making them out of bandannas and eventually everybody was making better ones and now … at least around here … most everyone is wearing them. And also, there are discarded masks everywhere. They’re the new potato chip bag or cigarette butt. At first I was photographing them on the street — but there were too many I thought for it to be interesting, but I’m compulsive, so I decided I’d only photograph them on the street in the rain. It got me out of the house. I photographed a lot of masks lying on the street in the rain and I was fascinated by both their sameness and their uniqueness — like a ruined building — the collapsed walls of this pandemic.

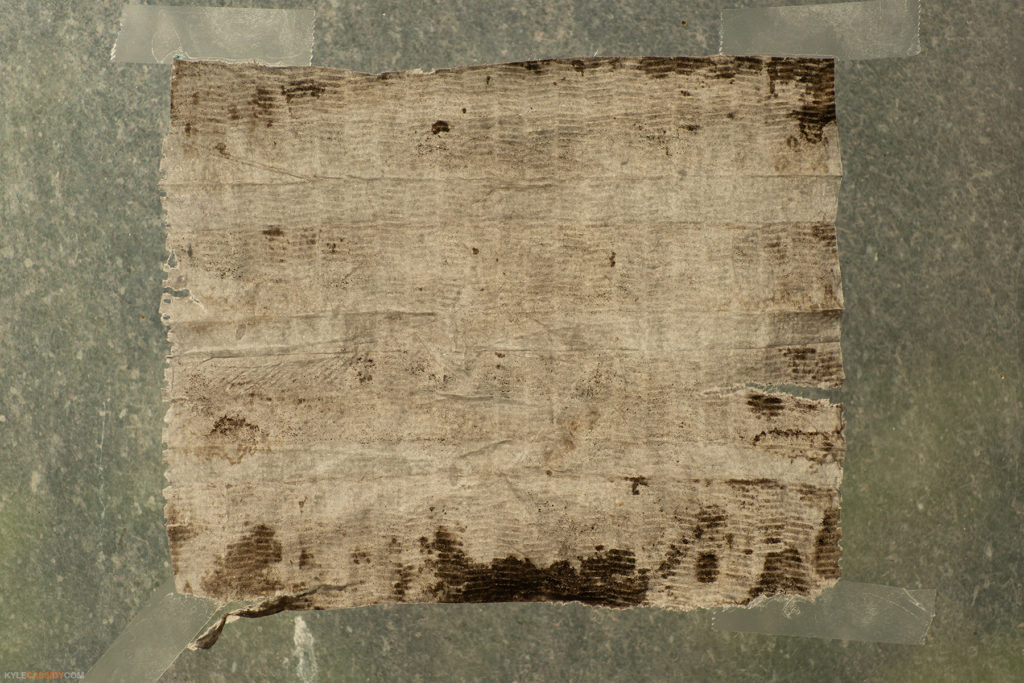

Then I got curious about how they worked and started reading about meltblown extrusion and nonwoven fabric and thought “if I was more process driven i’d be printing these images on surgical mask fabric.” I’m always amazed by those photographers who are like “I’m going to hollow out this pumpkin and use it as a camera body to take tintypes which I will develop in this wagon I haul through town”. But I wondered about printing images though the extruded meltblown layers of discarded surgical masks.

And there’s definitely something there. This is one more layer of between — it’s a thing that’s between us and the virus, it’s a thing that’s between us and each other. I’m also fascinated by the thought that there may be dead virus particles captured between these layers, somehow being touched by the light that ends up on these images.

So, I’ve been collecting, disinfecting, and photographing these layers — each unique and each one something that no person was ever expected to see — the fact that each time I look at the inner layer of a surgical mask it’s something that likely has never been seen by human eyes before and, were I not looking at the, probably wouldn’t be seen by human eyes ever — lest they be the eyes of an archaeologist a thousand years in the future who uses the surgical mask layer of stratigraphy as a way of dating artifacts.